It's a good thing this boy can make me laugh because, if I'm honest, I've been a little down lately. All will be okay, I know this, but in the meantime I'm quite grateful for C's silly sense of humor.

It's a good thing this boy can make me laugh because, if I'm honest, I've been a little down lately. All will be okay, I know this, but in the meantime I'm quite grateful for C's silly sense of humor.

Six Years

One glorious summer evening, near a beautiful lake, and in the company of a few close friends, we exchanged our wedding vows. We were full of hope and joy, picturing a future filled with happy wonder.

One glorious summer evening, near a beautiful lake, and in the company of a few close friends, we exchanged our wedding vows. We were full of hope and joy, picturing a future filled with happy wonder.

Six years have passed, and much of that time has been spent dealing with medical, developmental, and financial issues we never imagined. We haven't had a vacation. We haven't really had a break. And even tonight, our anniversary, we were unable to swing a babysitter and get out for a special dinner, just the two of us.

And yet…

As I sit here, six years later, I realize I wouldn't have it any other way. We have each other, and we have our little family. And despite all that's gone awry, each day is remarkable and beautiful, and I have no doubt the future will amaze us.

Happy Anniversary, Love.

What I Know About Fatherhood Now That I Have A Son On The Autism Spectrum

what-5

This post was originally published on Huffington Post for Father's Day.

When I learned we were going to have twins, I knew my journey as a father would be a little different. As if to prove the point, our boys arrived ten weeks early and spent over two months in NICU. While there, M developed a protein allergy that caused a life-threatening perforation in his intestines. Two weeks after C came home, all his systems shut down and I had to revive him with CPR. And there we were, in our apartment, two frightened parents with two tiny babies attached to heart monitors.

Yet this was just the beginning of our medical odyssey: C developed a very rare pediatric lung disease, and has spent the majority of his life with an oxygen tube slithering down the back of his shirt and trailing behind him. Then, when he was two years old, he was diagnosed with autism.

This last bit — autism — has proven to be the most challenging experience of all. It has also proven to be the most rewarding and the most enlightening.

Here are some of the things I've learned about fatherhood now that I have a boy with autism:

Worrying what other people think is a waste of time.

Before becoming a father I worried too much about the opinions of others. Then I went out in public wearing a backpack carrying an oxygen tank attached to my son's nose via a long plastic tube. Add to this picture standard toddler tantrums and autism-fueled verbal outbursts, and suddenly I began to think of myself and my family as a veritable freak show. That feeling lasted a short time, until it dawned on me that this is my life, this is my family, and I'm damn proud of us all. No one has to walk in my shoes, nor I in theirs, so worrying what they think of me — of us — is pointless.

what-1

My child is more than a diagnosis.

If I told you my son had cancer, you would think of him as a boy with an illness. When it comes to developmental issues, however, there is a tendency to define the child by the condition. So while it's true that C has autism, it's not the entirety of his being: there is the boy who loves to clomp around in my shoes and laugh at his feet; there is the boy who loves to give nose kisses and hug the cats and tell us that his favorite letter is Z; and there is the three-year-old who asks us how to spell the words "elephant" and "yellow," and sees the letters "CUXW" on an electrical box and proclaims, "Sounds likes saxaphone!" These things define C just as much, if not more, than his autism.

what-2

Reality rarely matches expectations, and that's a good thing.

Like many people, I painted pretty mental pictures for myself of what I thought parenthood would be like, and those pictures didn't include pediatric lung disease, autism, oppressive medical bills, insurance hassles, battles with schools, and so on. I understood parenthood wouldn't be easy, but like most people I assumed my family and I would be spared the really bad stuff. But here's where I got lucky: all of the tough stuff happened so quickly and so early there wasn't time to worry that my pretty mental picture didn't match my unfolding reality. My wife and I went into search and rescue mode almost immediately, and have remained there ever since. Of course there are moments of desperation and rage and envy, but the truth is that our crazy life has taught me to find joy and wonder and meaning in places where the old me — the me before becoming a dad — might only have found sadness and despair. Most of all, I've come to be very grateful for my life, warts and all.

what-3

Little accomplishments mean just as much as big ones.

Just before C received his official autism diagnosis, I confided in a good friend — who also has children on the spectrum — that I was having a hard time witnessing M excel while C fell behind. I told him I was constantly comparing my boys, and then feeling guilty for making the comparison. With great confidence, he assured me that in time C’s achievements would seem just as significant as M’s more advanced ones. I've learned that my friend was right. Any parent of siblings knows it's unwise to compare them, but when one child has a developmental disability (and, in our case, is a twin), those comparisons are a doubly unfair and unhappy proposition. But now comes the twist: with a lot of therapy, time, and normal childhood development, C is now ahead of his age — and his twin — in some key areas like reading and counting.

what-4

I have a purpose.

The first time I felt like a father happened before the boys were even born: I was installing car seats, and doing so slowly, methodically, while carefully reading the instructions (not my usual m.o.). The entire time I was thinking how important it was that I get this right, that I make sure my boys are safe when they're in the car. From that point forward, the responsibility of being a dad — of caring for and protecting my boys — has colored almost every aspect of my life. With C’s health and developmental issues, that sense of purpose has been amplified. And while I have high hopes for C, reason dictates that I should prepare for the possibility that he will be dependent on me for as long as I am alive. Instead of seeming overwhelming, this immense responsibility fills me with a sense of priority and purpose I never dreamed possible.

what-6

It's okay to need support.

I have always prided myself on my ability to go it alone, but this journey — which at times seems very isolating — has taught me just how much I truly, deeply need the help and support of others. It has been quite humbling. That's why one of the most surprising aspects of this experience has been the reaction, and lack thereof, of close friends. People I believed would be there for us have faded into the background for reasons I can't quite ascertain. Perhaps our situation makes them uncomfortable; perhaps they're fearful we might need too much; or perhaps they are simply busy with their own hectic lives. Whatever the case, the sting remains. Equally surprising, however, has been the reaction of other friends — some old, some new — who have come forward to offer their support in remarkable and wondrous ways. Their acceptance of us in general, and of C in particular, has been a salvation of sorts. Never a joiner, I've come to learn the value of community and the importance of asking for help.

The Future That Wasn't

In this lovely NY Times blog post, Joel Yanofsky writes of his family's preparations for their autistic son's impending bar mitzvah. The whole post is humorously touching, but I wanted to cite one line that really hit home:

When you have a child with autism you soon learn that you have to teach him everything, especially things most kids pick up intuitively — from playing with toys to carrying on a simple conversation.

This is it in a nutshell, the thing I keep trying to get at when I describe C's autism. You see, on their own the symptoms sound like a collection of personality quirks: repetitive behaviors, echolalia, lack of social reciprocity, lack of imaginative play, physical tics, etc.

The combined effect of these 'quirks,' however, is that C fundamentally does not understand how to interact with the world. Whereas his neurotypical twin is figuring things out on his own every hour of every day regardless of what we teach him, C needs to learn how to learn, if that makes sense. It's so much more fundamental.

And that is why, when Yanofsky writes this line, he really nails it:

The future is a scary place for every parent, but it’s especially so for the parent of a child with autism. No one has ever been able to tell Cynthia or me with any degree of certainty what our son is capable of.

We were cautioned by a doctor just after my son's diagnosis that we should never look too far into the future. "I've seen children we thought would do quite well who failed to progress," she said, "and I've seen children who were essentially written off who ended up surprising us all."

Sometimes I feel robbed of an imagined future, but I feel fortunate to have such a wonderful present.

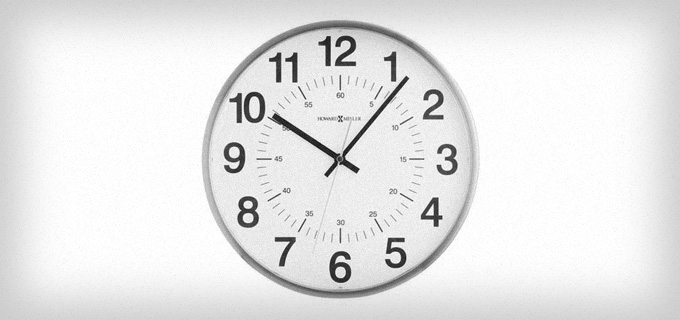

Tick Tock

We're running out of time.

In addition to all the stresses of having a child with health and developmental issues, there is the added worry that we're not doing enough right now, that precious time is slipping by.

We're told that the toddler / pre-schooler years are when the brain is most plastic; we're urged to consider these early years as the critical time to get as much help as much as possible; we're reminded that there is a tiny window of time when significant, lifelong changes can occur.

But there are only so many hours in a day, so many dollars in a bank account, so much energy parents can muster. There are only so many therapists we can manage, so many schools we can visit, so many tasks we can tackle. And then there are the obligations — jobs, family, etc. — that take time away from the work that needs to be done.

And the clock ticks on, every moment that passes an accusatory question: Did we do enough exercises today? Did we work hard enough to counteract the effects of autism? Or did we squander our precious time, and thus jeopardize a bit of our son's future?

And the clock ticks on, every moment that passes an accusatory question: Did we do enough exercises today? Did we work hard enough to counteract the effects of autism? Or did we squander our precious time, and thus jeopardize a bit of our son's future?

I believe there could never be enough time to do all the work that's needed, to take all the steps required, to try to set C on the right course. Sometimes I feel I'm in a state of panic.

If I'm not careful, I can become short with people I believe to be wasting my time. I feel guilty for the tiny bits of time I spend on myself throughout the day, so I try to rationalize them by saying those moments on Facebook or walking to and from the subway are helping me stay sane. I even look upon keeping this blog as a bit of a guilty pleasure.

I'm constantly loading my Instapaper account with articles on autism: scholarly, scientific, anecdotal, anything that will provide more insights, more understanding, more hope.

We don't (and can't) take a vacation, and haven't for several years. We rarely enjoy the so-called "date night." Instead, when the boys go to sleep, we eat our dinner and talk about C, his progress, his therapies, and what his future might hold.

I wish, for just one day, we could take a break from it all.

But the clock doesn't stop, so we can't either.